9-5 = Modern Slavery: Why Wage Labor Isn't Natural (And What We Can Do About It)

We've normalized spending 40+ hours per week exchanging our labor for survival—and we call this freedom. But what if the entire premise is broken? What if wage labor isn't natural, inevitable, or the only way humans can organize economic life? There's another way. I'm building it.

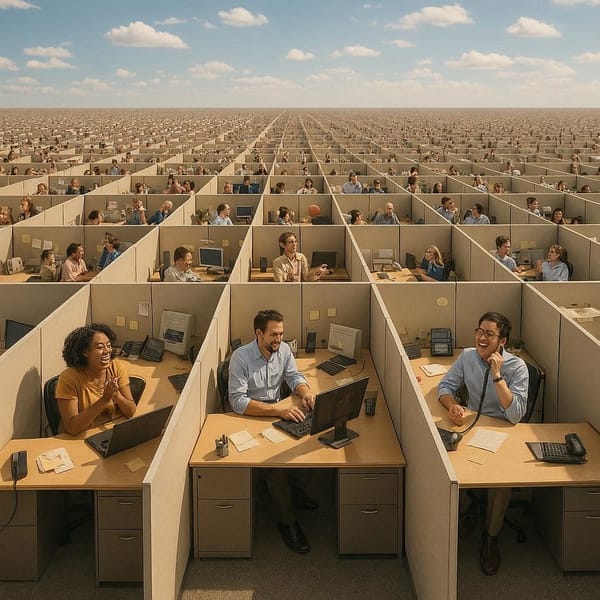

Picture this: Every weekday morning, millions of people wake up to alarms set earlier than their bodies naturally want to rise. They prepare themselves—shower, dress in specific clothing deemed appropriate by unwritten rules—and travel to buildings where they'll spend the next eight to ten hours performing tasks determined by others. They do this in exchange for currency that they'll use to purchase food, shelter, and other necessities. They repeat this pattern five days out of every seven, roughly fifty weeks per year, for forty to forty-five years of their lives. Only then—if they've saved adequately, if they're still healthy, if they survive that long—are they permitted to stop and live freely.

If you described this arrangement to someone from a radically different culture or time period without using our familiar vocabulary, they might find it bizarre. "Wait," they might say, "you mean people spend the majority of their waking hours, during the prime years of their lives, doing things they wouldn't choose to do, in places they wouldn't choose to be, at times they wouldn't choose to be there, just to earn the right to survive?"

"Yes," we'd have to answer. "But we don't really think of it that way. We call it 'having a job.' It's just... normal. It's what responsible adults do."

Of course, this probably seems like a ridiculous way to describe employment. Jobs are just normal. This is what everyone does. Questioning the basic structure of wage labor feels naive, like questioning gravity. But what if we've confused "normal" with "natural"? What if we've confused "how things currently are" with "how things must be"?

What "Wage Slavery" Actually Means (And What It Doesn't)

Let's start by defining terms, because "wage slavery" is deliberately provocative language that often triggers immediate resistance. I want to be clear upfront: I'm not claiming that wage labor is morally equivalent to chattel slavery. The comparison isn't about equating two forms of oppression but about identifying a specific structural similarity—dependence.

The term "wage slavery" describes a situation where people are dependent on wages for their survival, especially when those wages are low, working conditions are poor, and opportunities for upward mobility are limited. But I'd argue the definition should extend even to well-compensated professionals, because the fundamental structure remains the same: you must continuously exchange your labor for income, or you face loss of housing, healthcare, food security—the basic requirements for life.

This differs fundamentally from other forms of economic arrangement. In subsistence farming or hunting, you're exchanging your labor for direct goods—you plant seeds and harvest food, you hunt and eat meat. In independent craft or trade work, you're creating surplus value for yourself—you make furniture and sell it, accumulating capital and reputation that belong to you. But in wage labor, you're selling your time and effort in exchange for the temporary ability to continue surviving. The wage relation creates perpetual dependence rather than progressive accumulation of security or autonomy.

The most common objection here is obvious: "But isn't some form of work necessary for human survival? Haven't humans always had to work?"

Yes—but there's a critical difference between labor (the expenditure of effort to meet needs) and wage labor (the specific arrangement where you're dependent on selling your labor-power to an employer). Humans have always engaged in productive activity. What's historically recent and culturally specific is the arrangement where most people have no direct access to the means of survival (land, resources, tools) and therefore must sell their labor to those who do own these things in order to obtain currency to purchase what they need.

This distinction is essential: I'm not arguing against effort or productivity or contribution. I'm questioning a specific economic structure that emerged under particular historical conditions and serves particular interests.

How This Became "Normal": A Brief Historical Reality Check

Most people assume the 40-hour workweek and employment-based survival emerged organically as the natural way humans organize economic life. We imagine that people have always worked roughly these hours, in roughly this way, because this is simply what humans do.

The reality is startlingly different. Pre-industrial agricultural societies organized labor around seasonal rhythms and community needs rather than fixed schedules. Research on peasant life in medieval Europe suggests that despite the brutality and injustice of feudalism, peasants likely worked fewer annual hours than modern full-time employees—perhaps 1,400-1,600 hours per year compared to our 2,000+ hours. Their work was certainly harder physically, and I'm not romanticizing the past. The point is simply that the 9-5, five-days-a-week, 50-weeks-a-year pattern isn't some eternal constant of human existence. It's a recent invention.

The Industrial Revolution required fundamentally disciplining workers into factory time. People accustomed to task-oriented work—where you work until the task is done, then you stop—had to be trained into time-disciplined work, where you work for the duration of your shift regardless of whether there's meaningful work to do. This wasn't a natural transition. It required both ideological conditioning (the Protestant work ethic reframing constant labor as moral virtue, respectability politics linking character to employment) and material coercion (enclosure of commons that destroyed subsistence alternatives, vagrancy laws that criminalized unemployment, deliberately low wages that prevented accumulation).

Even the 40-hour workweek—which we treat as standard and reasonable—was established through bitter labor struggle in the early 20th century. Workers were demanding eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what they will. Employers fought this viciously. The 40-hour week was a compromise, not some scientifically determined optimal arrangement. And we still use this century-old standard despite massive increases in productivity through technology and automation.

Think about that: worker productivity has increased enormously over the past hundred years. In theory, we could produce the same output in far fewer hours, or produce much more in the same hours. Instead, the gains from increased productivity have flowed almost entirely to capital owners while workers continue putting in the same 40+ hours. Why? Because once this arrangement became normalized, we stopped seeing it as one possible way to organize economic life and started seeing it as the only way, as simply "what people do." Anyone who questions it seems naive or entitled rather than reasonably skeptical of an arbitrary historical development.

Who Benefits? Following the Incentives

The normalization of wage labor isn't an accident, and it's not a conspiracy. It's a feature of a system organized to benefit those who own capital—land, resources, means of production, intellectual property, investment portfolios. When you can own capital, you benefit immensely from a large population that has no choice but to sell their labor to survive.

This creates the conditions for exploitation even in the absence of individual malicious actors. Even well-meaning employers who treat workers decently and pay above-market wages still benefit from workers' structural dependence. That dependence ensures a continuous labor supply and limits workers' bargaining power. If people could easily survive without wage labor—if they had guaranteed access to land, housing, food, healthcare—wages would have to rise dramatically to attract workers, and many jobs that currently exist only because labor is cheap wouldn't be economically viable.

The system is reinforced through consumer culture in ways that are almost elegant in their circularity. People locked into the wage-survival cycle need to continuously consume products and services, which drives demand for more wage labor to produce those goods, creating a self-reinforcing system. You work to earn money to buy things, many of which you need precisely because you're working: convenient lunch spots near offices because you don't have time to prepare food, professional clothing you wouldn't otherwise need, expensive coffee to combat exhaustion, therapy and stress-relief purchases to cope with workplace demands, time-saving services because you have no time. The system needs you buying things you don't truly need to keep you locked in needing to work.

This is why inequality isn't an unfortunate bug that could be fixed with better policies while leaving the fundamental arrangement intact—it's a predictable outcome of a system where some people own capital and most people sell labor. Over time, capital accumulates to those who already have it (because it generates returns without labor, through rent, interest, profit, and appreciation), while those dependent on wages struggle to accumulate capital (because wages barely cover survival and the consumption needed to participate in society). The gap widens structurally, not because the wealthy are necessarily greedier or more hardworking, but because of how the system functions.

Here's what's crucial to understand: this doesn't require conscious conspiracy. Individual capital owners may be generous, ethical people who genuinely believe the system is fundamentally fair, that anyone can succeed with enough hard work. Many of them worked extremely hard themselves. But their material interests align with maintaining a system where wage labor remains normalized and alternatives remain marginal or stigmatized. This is why you see massive cultural investment—through education, media, political messaging—in the idea that wage work is inherently virtuous, that people who don't participate are lazy or parasitic, that there is no alternative.

When someone says "there is no alternative" to wage labor, what they're really saying is "I cannot imagine an alternative that preserves my current advantages." And perhaps they're right—perhaps truly transforming how we organize economic life would disrupt existing hierarchies and distributions of resources. But the fact that the current arrangement benefits some people enormously doesn't make it natural, necessary, or optimal for human flourishing.

The Psychological Toll: What We've Lost

Beyond the structural analysis, there's something else worth examining: what the wage-labor arrangement costs us in terms of lived experience, psychological well-being, and human potential.

Consider what you lose when your survival depends on continuous employment. You lose the ability to respond to your own rhythms and needs—to rest when you're genuinely tired, to work intensely when you're inspired, to take time when you're processing grief or illness or major life transitions. You submit to arbitrary authority in the workplace, performing emotional labor to appear enthusiastic about tasks you may find meaningless, managing your affect to avoid being seen as difficult or uncommitted. You fragment your attention across eight to ten hours even when your actual productive work might require only three or four hours of focused effort. You maintain the pretense of busyness.

The exhaustion compounds over time. After a full workday plus commute, many people are too depleted for genuine rest, creativity, or deep connection. Friendships become difficult to maintain when everyone has limited free time and energy. Family relationships get squeezed into margins—rushed mornings, exhausted evenings, weekends consumed by errands and recovery. The people you love most get the version of you that remains after work has taken what it needs.

Then there's the retirement trap, that distant promise that makes the whole arrangement supposedly bearable. "Yes, you'll spend 40-45 years doing this, but then you'll be free to actually live your life." Except you'll only be free if you've managed to save adequately—and most people don't, because wages barely cover current expenses and consumer culture constantly encourages spending. You'll only enjoy that freedom if you're healthy enough—and many people aren't, because decades of stress and sedentary work take a physical toll. You'll only experience it if you survive that long—and many people don't reach retirement, or die shortly after, never having gotten to live freely during their prime years.

We've normalized the idea that you get to actually live your life only after you're too old to fully engage with it. Think about how absurd that is. Your twenties, thirties, forties, fifties—potentially your most energetic, healthy, capable years—are spent working. By the time you're "free," your body may be failing, your energy diminished, your opportunities for adventure or physical challenge or even just sustained focus significantly reduced.

Perhaps most insidiously, this arrangement shapes consciousness itself. When your survival depends on pleasing employers, you internalize that dependence. You learn to suppress criticism, to manage your personality and presentation, to make yourself maximally useful and minimally troublesome. Over decades, this can erode your sense of autonomous selfhood. You forget what you actually want because you've spent so long focused on what others need from you. You lose touch with your own values because you've been optimizing for someone else's values—productivity, efficiency, profitability, growth.

The isolation embedded in this model compounds everything else. When everyone is working full-time in different locations, on different schedules, community becomes difficult. You're tired. You have limited free time. You're geographically dispersed from extended family and long-term friends. The nuclear family becomes the only reliable social unit, which places enormous pressure on those relationships—romantic partnerships are expected to provide emotional intimacy, intellectual stimulation, practical support, sexual fulfillment, and co-parenting, all while both partners are exhausted from work. People without families, or whose family relationships are strained, often find themselves profoundly isolated.

This is what we've traded for "normal." This is what we call "responsible adulthood."

"But Don't We Need to Work?": Addressing the Obvious Objection

At this point, you're probably thinking: "Okay, maybe wage labor has serious problems. But what's the alternative? Don't humans need to work to survive? Food doesn't grow itself, houses don't build themselves, infrastructure doesn't maintain itself. Isn't this just complaining without offering solutions?"

Fair question. Let me be absolutely clear: yes, humans need to engage in productive activity. Food must be grown or acquired, shelter must be maintained, goods must be produced, care work must be done, infrastructure must be tended. The question isn't whether labor is necessary—it obviously is. The question is how we organize that necessary labor and how many hours of our lives it actually requires.

Here's what's become clear to me: the current arrangement is wildly inefficient in terms of converting labor hours into human flourishing. Consider how much wage labor produces things nobody actually needs—products designed for planned obsolescence so you'll buy replacements, redundant brands competing for market share, an endless proliferation of gadgets and goods that mostly end up in landfills. Consider how much labor maintains artificial scarcity—intellectual property lawyers ensuring knowledge stays locked behind paywalls, financial services creating and managing complexity that primarily serves to extract wealth, massive marketing and advertising industries whose purpose is manufacturing desire for things people wouldn't otherwise want.

David Graeber's concept of "bullshit jobs" is relevant here. Through surveys and interviews, Graeber found that a large percentage of workers in wealthy countries believe their own jobs are pointless—that if their position disappeared, nothing important would be lost. We're not talking about janitors or nurses or farmers (who consistently find meaning in their work). We're talking about middle managers, corporate lawyers, PR consultants, telemarketers, brand strategists—people spending 40 hours per week doing work they themselves recognize as contributing nothing meaningful to human welfare.

Meanwhile, the actual labor needed to meet genuine human needs—growing food, maintaining infrastructure, caring for children and elderly, teaching, creating culture, healing—could potentially be accomplished in far fewer hours per person if organized cooperatively rather than through market competition and profit extraction. I'm not claiming to have definitive proof of exactly how few hours would be required—that's something we'd need to discover through experimentation. But consider: if we eliminated bullshit jobs, reduced consumption of unnecessary goods, organized labor cooperatively to minimize redundancy, shared resources efficiently rather than each household maintaining separate infrastructure... how much would we actually need to work?

My hypothesis, informed by both research and lived experience in various community settings, is that virtually all human needs could be met with somewhere between 5 and 15 hours of work per person per week, and that number only gets smaller the more people who are involved and the better the automation. Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe it's 20 hours. But even 20 hours per week is half the current standard, which means half your waking hours returned to you.

There's another way to organize economic life—one where you're not dependent on continuously selling your labor to survive, where your basic needs are secure through collective organization, where you work cooperatively toward shared goals rather than competing for wages. Where your contribution is valued but your survival doesn't depend on your productivity. Where you have genuine autonomy over your time.

It's called intentional community, and it's what I'm building.

An Invitation

I won't pretend that leaving wage labor entirely is immediately possible for most people right now. The system is structured to make alternatives difficult, and recognizing that structure is honest, not defeatist.

But recognizing that wage labor isn't natural, isn't inevitable, isn't the only way humans can organize economic life—that recognition is the first essential step. Once you see the current arrangement as constructed rather than given, as serving particular interests rather than being neutral, you can begin imagining and building alternatives.

I'm documenting my entire journey toward economic freedom through intentional community. The research phase, where I'm learning from existing communities and studying what works and what doesn't. The planning phase, where I'm figuring out land acquisition, legal structures, governance models, economic systems. The building phase, where I'll actually create a community space. The living phase, where I'll share what it's actually like to live outside the wage-labor paradigm—the joys, the challenges, the unexpected discoveries.

If you've ever felt that something about the way we're all living doesn't quite make sense, that there should be another way, that spending your best years working for survival feels like a profound waste of human potential—you're not alone. And you're not wrong.

Follow along. Question everything you've been told is "just how things are." And when you're ready, maybe you'll build something different too.

The future doesn't have to look like the past. We get to choose.

This is the first post in the Intentionally series. Subscribe for updates on the journey toward economic freedom and life beyond the wage.