A Critique of Atomistic Individualism

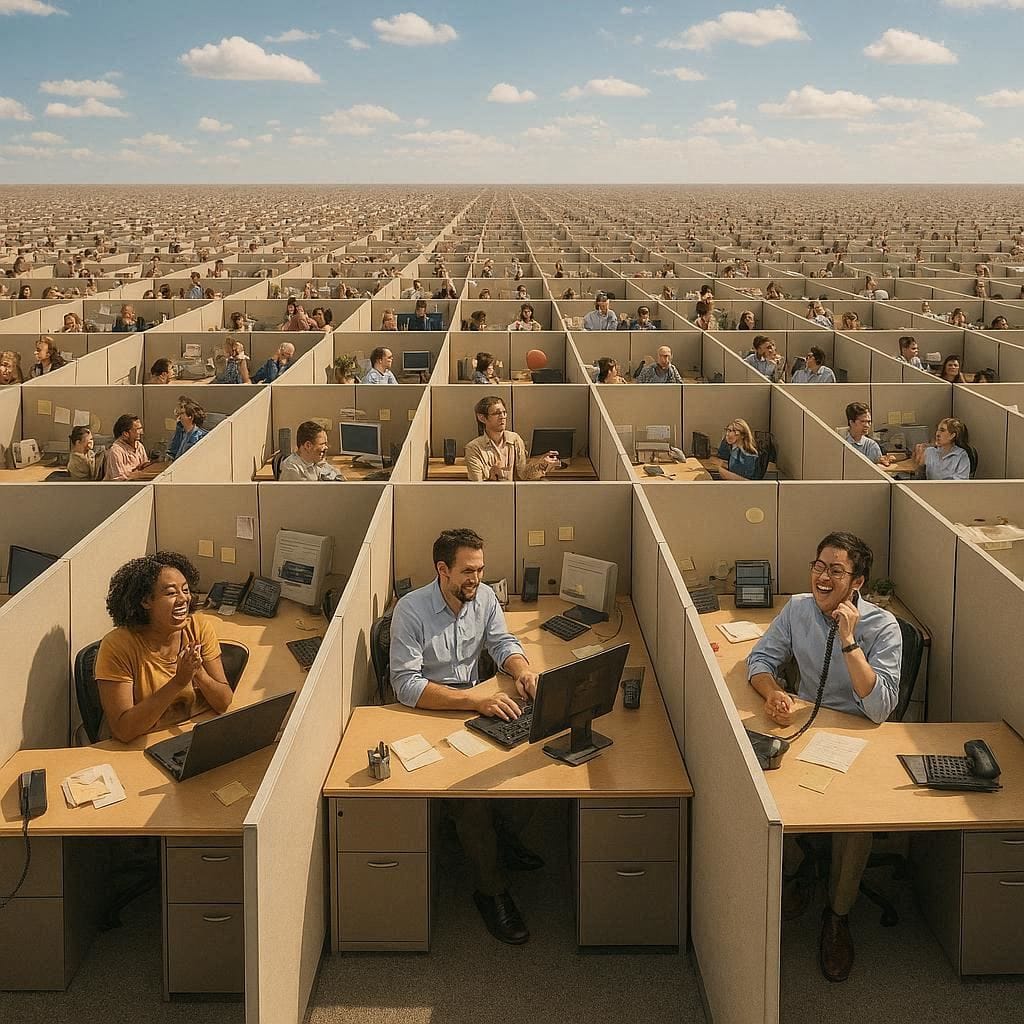

We're taught that individual freedom should always come first, but this misses a basic truth: we're fundamentally interconnected. Pretending we're isolated atoms makes it impossible to solve problems requiring cooperation and can't explain why we care about things beyond ourselves.

We often take for granted the idea that each person is a separate, self-contained individual whose personal freedom and self-interest should come before the needs of any group. This philosophy—called atomistic individualism—is so embedded in modern culture, especially in Western societies, that it can seem like simple common sense. But this way of thinking has serious problems, both in how it describes reality and in the values it promotes.

The first issue is that atomistic individualism gets the basic facts wrong about what people actually are. It treats us as if we start out as complete, independent individuals who then decide whether to form relationships and join groups. But that's not how human beings actually develop. We don't begin as self-sufficient atoms and then choose to connect with others—we're born completely helpless and become individuals only through years of relationships and social learning. Everything that makes you "you"—your language, your values, your ability to think and make choices—comes from growing up embedded in families, communities, and cultures. The independent, choosing self that individualism treats as the starting point is actually the result of specific social conditions, not something we naturally are before society shapes us.

This backward understanding of human nature leads to practical problems in how we organize our world. Economic systems built on individualism assume that if everyone pursues their own self-interest, things will work out well for society overall. But this ignores how our choices are constrained and shaped by the systems we live in, and how individual actions can add up to collective disasters. Climate change is a perfect example: when millions of people make individually reasonable choices about consumption and convenience, the cumulative effect threatens everyone's survival. The individualist framework keeps telling us that personal freedom and choice are paramount, even as this approach leads us toward catastrophe.

Atomistic individualism also can't make sense of some of our deepest values and most meaningful choices. Think about parents who would sacrifice everything for their children, or people who take lower-paying jobs because the work matters to them, or those who risk their safety to fight for justice. These aren't mistakes or failures of rationality—they're expressions of what makes life meaningful. But if you believe individuals should always prioritize their own interests above everything else, these choices look irrational. The framework can't account for the fact that we often care about things—our families, our communities, our principles—more than we care about our individual welfare. And this isn't a bug in human psychology; it's a central feature of how we actually experience meaning and value.

The problem becomes even clearer when we face challenges that require everyone to work together. Managing pandemics, preventing environmental collapse, ensuring new technologies like artificial intelligence benefit rather than harm humanity—these all require coordinating our actions in ways that sometimes conflict with individual freedom and immediate self-interest. When the governing philosophy says individual choice should always win, we have no good way to solve problems that require collective action. Markets and voluntary cooperation—the individualist's preferred tools—work well for many things, but they systematically fail when it comes to shared resources, long-term threats, and situations where individual and group interests pull in different directions.

None of this means we should abandon personal freedom or treat individuals as worthless. The alternative to atomistic individualism isn't totalitarianism or forced collectivism. Rather, it's recognizing a basic truth: we are fundamentally interconnected, and pretending otherwise makes it harder to build the kind of world where both individuals and communities can actually thrive. We need ways of thinking and organizing society that acknowledge how deeply we depend on each other, while still respecting the real value of personal autonomy and individual dignity. The goal isn't to choose between the individual and the group, but to understand that these are two sides of the same coin—that human flourishing requires both personal freedom and strong communities, both individual agency and collective responsibility.

The dominant individualist ideology isn't just a neutral description of reality or an obvious ethical truth—it's a particular worldview that emerged from specific historical circumstances and serves certain interests. Recognizing its limitations is the first step toward developing better ways of understanding ourselves and organizing our shared life together.